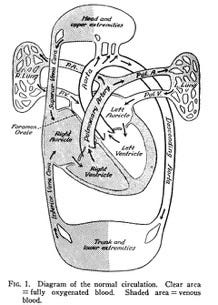

The human heart – to which we ascribe love, compassion and life itself – is a remarkable organ. Most of us learned that the heart is a muscle with four chambers whose collective job is to move our blood first to the lungs so that it can be enriched with oxygen, and then throughout our body so that oxygen can be released and used. The heart is a pump that conveys the essential content of the air that we breathe to every cell in our body.

Before birth – as each of us develop and grow in our mother’s womb – there is no full dress rehearsal for the heart’s performance. It is never called upon to send blood to the lungs for oxygenation. As with many things which first sustain us, that oxygen comes from our mothers. It is only with our first breath that the heart is mandated to alter the flow of blood to include our lungs.

When babies are born with certain abnormalities of heart anatomy, the blood is not adequately oxygenated before flowing into the body’s circulation. The result is that these infants have cyanosis and appear blue. Often such abnormalities are life-threatening and were not surgically correctable until the 1940’s, 1950’s or 1960’s, depending on the specific abnormality. At an international conference of physicians, held in London in September, 1947, a pediatrician delivered a report of a new surgical procedure that had successfully helped infants and children with Tetralogy of Fallot, one of the first identified causes of “blue baby syndrome”.

The pediatrician was Dr. Helen Taussig, from the Johns Hopkins Hospital, who was the first pediatric cardiologist in the United States. The surgical procedure was conceived by Dr. Taussig and was performed by Dr. Alfred Blalock, although most of the credit for the technique belongs to Mr. Vivien Thomas,[1] an African-American man who was the assistant to Blalock at Vanderbilt University and then at Johns Hopkins. His formal education ended at his high school graduation, yet he became a pioneer in cardiac surgery.[2] Thomas directed Blalock’s research lab and first perfected the life-saving procedure on dogs. The Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt became a landmark in surgical correction of congenital heart disease, performed on over 600 patients by the time Dr. Taussig’s presentation mentioned above was published in the British Heart Journal in April, 1948.

By the time I started medical school in 1972, Helen Taussig was a legend. She had retired in 1963, but remained at Johns Hopkins as Professor Emerita. For her distinguished career, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson the year after her retirement. I had no idea that, shortly after beginning medical school, I would have a role in editing and summarizing some of her life’s work. But first it is important that I tell you more about Dr. Taussig, before I tell you about how the task fell into my hands.

Helen was born in 1898 – the same year as my paternal grandfather. We were two generations apart and as far apart professionally as a medical student and a famous retired Professor could be. She grew up in Cambridge, MA. Her father taught economics at Harvard University. Her mother had been one of the first students at Radcliffe College, but she died from tuberculosis when Helen was 11 years old. Upon graduating from high school, Helen studied at Radcliffe, but she completed her final two years of college at the University of California at Berkeley.

She returned to Boston to study medicine – but, because she was a woman, Helen was directed first into public health at Harvard, and then at Boston University. At that time, neither school would grant medical degrees or graduate degrees to females. So Helen pursued medical studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and she received her M.D. degree in 1927. Her achievement was also remarkable because she had a significant hearing loss after a childhood flu infection; by the time she graduated from medical school, she depended on lip-reading and bulky hearing aids. During her early pediatric training, she was able to learn as much from “feeling” the heart when she examined the chest of a child with her fingertips as others learned from listening to a child’s heart with a stethoscope.

Dr. Taussig spent her entire career as a physician at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, specifically in the Harriet Lane Clinic for Children, where she ran the Cardiology Clinic. Her initial focus was on rheumatic heart disease,[3] a common long-term consequence of rheumatic fever caused by strep throat and other streptococcal infections. (Penicillin would not become commonly available to treat streptococcal infections until 1943.[4]) When fluoroscopy – a new x-ray technique that provides real-time moving images – became available to the medical community, Dr. Taussig learned how to use this technology for studying and diagnosing different types of heart disorders.

Dr. Taussig observed that some children with certain congenital heart abnormalities died shortly after birth when their bypass duct closed. She observed that some children with congenital heart disease did better (i.e. have less cyanosis and better oxygenation) if they have a persistent duct between the right and left sides of the heart. She therefore approached the surgeon, Dr. Alfred Blalock, with the idea of creating a duct for the “blue babies” whose ductus arteriosus had closed normally. This observation led to a counter-intuitive approach of allowing some blood to reach the lungs via the aorta, thereby improving overall oxygenation sufficient to support life.[5] Over subsequent years, the surgical procedure used to create this vital duct was applied to an expanding number of congenital heart abnormalities. And after the end of her clinical career, Dr. Taussig was ready to begin publishing her follow-up studies of patients who had undergone the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig procedure.

In the strangest of ways, this is why our paths crossed. I began my second year of medical school with an interest in the Johns Hopkins Medical Journal, which was then edited by Dr. A. McGehee Harvey, who had previously spent 27 years as Chairman of the Department of Medicine and Physician-in-Chief at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. I made an appointment to meet with Dr. Harvey, expressing an interest in joining the editorial staff. In some ways, I approached this goal as I had in college, where I was a contributor to one magazine and then in the next year an editor of another.

It seemed only reasonable to me that I should apply some of these skills to the medical arena. Dr. “Mac” Harvey was more approachable than I had expected. He seemed intrigued by the somewhat brazen offer of my services, given that the Journal’s editorial staff had previously included only faculty. At the beginning, before I was later given the additional responsibility of soliciting and editing material for a Clinical Conference that was to be included with each issue, my job was to edit selected articles that had been accepted for inclusion, and get them ready for publication. In retrospect, I have no idea how I found time to do this and keep up with my regular medical school responsibilities.

When I was asked to edit several articles submitted by Dr. Helen Taussig, I was honored! I was also surprised that this task would be given to me. However, once I began reviewing them, I was again surprised. The articles were not well organized; they were not well written; and I told Dr. Harvey they were beyond the help of an editor. He smiled a smile that was uniquely his, concealing what I did not then know about Dr. Taussig – she had dyslexia. He said simply, “Then re-write them.”

How could it be that someone so famous, so highly respected as a compassionate pediatrician, so creative as to conceptualize a life-saving operation based upon her observations of cardiac physiology – how could it be that she could not write clearly? In laboring to re-write her lengthy articles to prepare them for publication, I gradually came to appreciate her years of astute clinical observation of these children who underwent surgery. She was not an academician who measured her achievement by the number of articles published. Dr. Taussig’s achievements were her excellent medical care and compassion for children and her long-term follow-up of these pediatric patients after their surgery for congenital heart disease.

The two lessons I learned from Dr. Helen Taussig were ones that I have subsequently learned many times over. It is wrong to judge someone for what they cannot do, and wiser to look beyond a person’s limitations to see the remarkable ways in which they think, adapt, and problem-solve. Unconventional or novel ways that differ from how we might approach a problem could lead to excellent innovations or solutions! And, it is for us to see that each person is uniquely gifted. Some natural or adaptive talents are not always valued like academic success or financial success, but they contribute greatly to society and are worthy of recognition and respect.

Opa

[2] Watch Something the Lord Made (2004) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sRimw4D8kOo

[3] https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/rheumatic-heart-disease

[4] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5403050/

[5] https://resources.jax.org/jax-blog/women-in-science-helen-taussig-1898-1986

So interesting. As I read your words I kept thinking how profound Taussig’s work is with spiritual imagery and implications. Her procedure is akin to my own work on people’s spiritual hearts. Blockage. No life. Dead before they even lived. Yet, I was the witness to blockage breakthroughs and new hearts of flesh, not stone; even resurrections. I loved this! Thank you. What a seat you’ve had to be a witness to all you write now. So rich and a gift to us all!