Finding the Book

Letter #98

Gram and I were recently invited to attend “Grandfriends Day” for our grandson, who is in 7th grade. After the introductory program, we were dismissed to his classroom, where each of the students was asked to introduce their guests, giving their names, where they lived, what the student called them, and what they liked to do. In general, the introductions went well, although our grandson’s friend – known to be one of the smartest in the class – had to ask his grandparents’ help for three of the four questions. Our grandson, however, had a confident answer for each . . . but he surprised us when explaining what we liked to do. “They read books,” was his quick, droll response.

I suppose that was fair, given the number of books in our house, although Gram and I actually have interests that extend well beyond reading. Our grandson visits us often and he sees our book collection, which takes up the longest wall of our living room and two walls of the office that Gram and I share. And then there are usually stacks of books on our dining room table and next to our bed. (But know that we do not sit and read when we have visitors!)

At the present time, we have about 2000 books. One reason for this is that we haven’t moved in almost 8 years. An advantage of relocating every four years, as we have historically done, is that it forces us to thin out our library, so that we don’t have to box up a ridiculous number of books when moving. But the other reason – at least for me – is my growing sense that curating a library is important. It is a legacy of who Gram and I are and a visual of something we value.

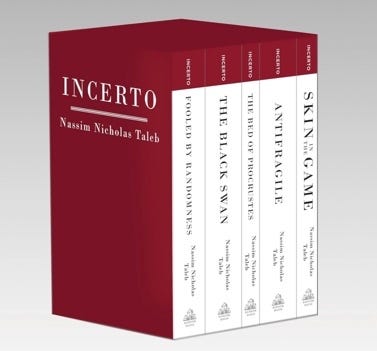

If you were to ask me why I believe this, especially since public libraries are so readily available and many of our books – as well as thousands more – are available online, I would give five reasons . . . and Gram would add a sixth. First, it is celebratory – we are excited to share books that have been meaningful to us or that better explore an issue that we have thought about or tried to explain. The opportunities to do this come by serendipity and at the most unexpected times. Or, in some cases, there are books that we have so enjoyed that we wish to read them again. Second, it is aspirational. Our library includes books that we have not yet read, but intend to read (or hope to read if we live long enough). Nassim Nicholas Taleb has said that the value of a personal library lies in constantly reminding us of what we do not yet know.[1]

Third, it is protective – the preservation of important perspectives that may someday be hard to find. Until recently, I never had a concern that ideas would no longer be free to roam on the open range of thought and discussion. It now seems that books are being herded into a corral of cultural or historical revisionism, and branded as acceptable . . . or banished if not. Fourth, it is fraternal – a way to know and spend time with great people and great thinkers – even from generations long past – and to be a time traveler getting a sense of what life and issues were like in bygone days. And fifth, it is survival – providing reference to essential skills or ideas that may be necessary to thrive after the collapse of the internet, AI, or even civilized society. Several of these reasons are encapsulated by the Japanese word tsundoku – the habit of acquiring books without necessarily reading them – and preparing for the improbable.[2]

My hero in this regard is Umberto Eco, author of the medieval mystery Name of the Rose, who reminded us of their importance, saying, “libraries are mankind’s common memory.”[3]

Finally, Gram would add humor – a necessary addition for lifting our spirits during difficult times. In addition to the dry wit of Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, Will Rogers and H.L. Menken, our library contains books by Roz Chast, a cartoonist featured in the New Yorker Magazine, as well as Far Side books by Gary Larson, Calvin & Hobbes books by Bill Watterson, and Zits books by Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman.

Neither Gram nor I have an expansive memory, and from her I often heard the question, “Where is that book . . .?” Once we reached the point that our collective memory was no longer sufficient to find what we were looking for, I knew it would be a good idea to better organize our books. I therefore resolved at the beginning of 2025 to catalogue all our books by the end of the year. For the most part, I have been successful.

You probably haven’t given much thought to how “stacks of books” evolved into “bookstacks”. This arcane detail dates back to the end of the 19th century, about the time my paternal grandfather and Gram’s paternal grandparents were born. Creating storage to shelve books upright became a wonderful alternative to stacking them on top of each other. It was an engineer’s solution to clutter, made necessary for libraries to be able to hold 10’s or 100’s of thousands of books. In the United Kingdom, credit for this innovation goes to James Osborne Smith,[4] but in the United States, all-metal shelving was designed by Bernard Richardson Green,[5] who introduced it in the new Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, which was completed in 1897.[6] In the early days, the “stacks” were primarily for storage, and separate from the reading rooms of a library. Now, most libraries are “open stack” – available for all patrons to browse.

Finding a solution to shelving and storing books solved one problem. But another was setting up a way to find them. Thomas Jefferson used a system that was derived from Francis Bacon’s classification of all knowledge into three areas – Memory, Reason, and Imagination, which he described in The Advancement of Learning published in 1605. Jefferson renamed these three areas as History, Philosophy, and Fine arts, and then he divided these into a total of 44 subclasses. While serving as the United States minister to France in the 1780’s, he acquired thousands of books in Europe and built the largest collection of books in America by the time he returned to his home in Monticello, Virginia.[7]

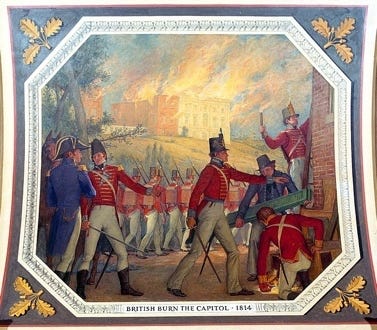

When the British invaded and torched Washington, D.C. – burning both the White House and the U.S. Capitol – in August, 1814, they also destroyed the 3000-volume Library of Congress.[8] The following month, Jefferson wrote to Congress and offered them his 10,000-volume library as replacement. Congress debated the offer, and purchased almost 6500 books, excluding those written in a foreign language or others considered irrelevant for use by Congress.

The new Library of Congress mostly continued Jefferson’s classification system. However, in 1897, when the Library held a million books and the new Thomas Jefferson Building was being completed, a decision was made to modernize the classification system.[9] Given the size of the task, manual reassignment of classifications progressed over years. An alpha-numeric system was proposed by Charles Martel, an immigrant from Switzerland, who became the chief classifier of the Library of Congress (and later a consultant helping to catalogue the Vatican Library).[10]

In 1901, books concerning the history of America were classified with the letter E (books about the United States) and F (books about local history or non-English America). By 1905 books about science were classified with the letter Q. By 1910 books about philosophy and psychology were classified with the letter B. At the same time G was used for geography, H for social sciences, J for political science, N for fine arts, R for medicine, T for technology, and U for military science. By 1916 books about world history were classified with the letter D. Books about language and literature – whether poetry or prose – were gradually assigned the letter P. Ultimately, 21 of the letters in the alphabet have been used, with books about law – assigned to the letter K – being added last in 1969. Today, this classification system uses one or two letters of the alphabet, followed by numbers. It has been available online for over 20 years, and it is updated daily.

Nevertheless, the Library of Congress classification wasn’t the one that Gram wanted to use. She grew up using the Dewey Decimal System, which is the system most widely used in the world and the one most often found in public libraries. And it is older than the Library of Congress classification system. It was initially designed by Melvil Dewey in 1873, while he was working at Amherst College. It has since been revised numerous times. Basically, it classifies books about philosophy and psychology in the 100’s, books about religion in the 200’s, social sciences in the 300’s, language in the 400’s, science in the 500’s, technology in the 600’s, arts and recreation in the 700’s, literature in the 800’s, and history and geography in the 900’s.[11]

I was biased toward the LOC classification system because it more easily accommodates new subjects and the catalogue number is more likely to be printed below the copyright date of a book than is the Dewey Decimal number. Since the project was mine, Gram ultimately deferred to me. She preferred to work in the kitchen and cook, while I labeled, catalogued and shelved every book that we own.

As we approach the end of 2025, the last of our books are almost cartalogued. Over half the volumes in our library are now tagged for B (which since 1927 also includes religion), D and E (world and American history), and P (literature). As I survey the shelves, I find it interesting to see what books become neighbors. Who would have guessed that Steven King’s On Writing would sit next to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22? Or that Nichol’s Death of Expertise would sit next to Ord’s The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity? Or Miroslav Volf’s Exclusion and Embrace next to Michael Walzer’s Just and Unjust Wars? Classifications sometimes highlight relationships between books that I had not considered.

As our books were being tagged, I created a database for them in Notion, an incredibly flexible and useful tool that allows Gram or me to look up – on my desktop computer or our phones – a book by title, author, or subject. So, now, when Gram asks “Where is that book . . .?”, I respond with the same words that she has used hundreds of times in responding to questions from our children who were looking for a quick answer: “Look it up!”

Opa

[1] Author of The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2010)

[2] https://nesslabs.com/antilibrary

[3] Umberto Eco: A Library of the World. Trailer at:

[5] The Building for the Library of Congress (1897) at http://bit.ly/3XHDuzq

[7] https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jefflib.html

[8] “The Burning of Washington” by Jason A. Clark (2024) at http://bit.ly/4a5hRAj

[9] https://www.loc.gov/aba/publications/FreeCSM/historicalnotes.pdf

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Martel_(librarian)

[11] https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/oclc/dewey/resources/summaries/deweysummaries.pdf

Love how cataloging forces you to confront the weird adjacencies between books. I did something similar couple years back (not quite 2000 tho) and ended up grouping my sci-fi stuff alphabetically cuz the LOC numbers felt too granular for fiction. The tsundoku reference is spot on tho, always end up with more shelf space dedicated to books I havent read than ones Ive finished.