When I accepted a position with the Indian Health Service and our young family moved to northern Arizona, I thought it would be a good idea to learn to speak the language of those I would care for. This was not essential when working with the Hopi people, because they were all comfortably conversant in English, even as they continued to speak their traditional language which is more closely related to Ancient Aztec than to other Pueblo languages.

It was a good idea for interacting with Navajo patients, however. Because the Hopi Reservation is completely surrounded by the much larger Navajo Reservation, the Navajos living in the deep interior of the reservation often had less exposure to English than those living closer to border towns on the periphery. Often, our older Navajo patients had no ability to communicate in English.

This made the role of Navajo translators critically important. Our translators not only communicated vital information that treating physicians sought, they also bridged the cultural divide between traditional Navajos and bilagáanas (white Americans). I admit that I was occasionally frustrated by asking a simple medical question, which was often followed by a 5-minute conversation between translator and patient (to discuss travel, weather, family, or current tribal affairs) before getting a basic response, like “yes” (aoo,) or “no” (dooda).

I learned some basic Navajo terminology, like “open your mouth” and “wider!” But my ability to learn on the job was far from sufficient. I felt the need to learn the Diné bizaad (the People’s language). So I did what any diligent bilagáana would do: I signed up for a class.

The language course was held on Monday evenings in Ganado, Arizona, a community on the Navajo Reservation 44 miles east of Keams Canyon on the Hopi Reservation, where we lived and worked. The drive on State Route 264 was always at the end of a long Monday clinic, and – because the Navajo Reservation observed daylight savings time, while the state of Arizona and the Hopi Reservation did not – Ganado was a time zone away.

I was surprised that the majority of the 20 or so students in my class were young adult Navajos, learning to speak their own traditional language. Our teacher was a fervent educator named Teddy Draper. But his enthusiasm for the subject did not make the class easy. I had studied Latin in high school and Russian in college, so I considered myself sufficiently flexible to undertake a new language. But I was wrong – very wrong!

Navajo was not traditionally a written language, and the first written forms appeared in the 1930s. It is of Athabaskan origin (related to the language used by indigenous people of the interior of Alaska). It is a tonal language with high, rising, falling and low tones.[1] Teddy Draper was as eager to teach the language to young Diné as they were to learn it. But the language, like the philosophy that is intertwined with it, is foreign to the typical American mind. I have, for example, always tended to see people and objects from the top down. The Navajo way is to see life from the ground up.

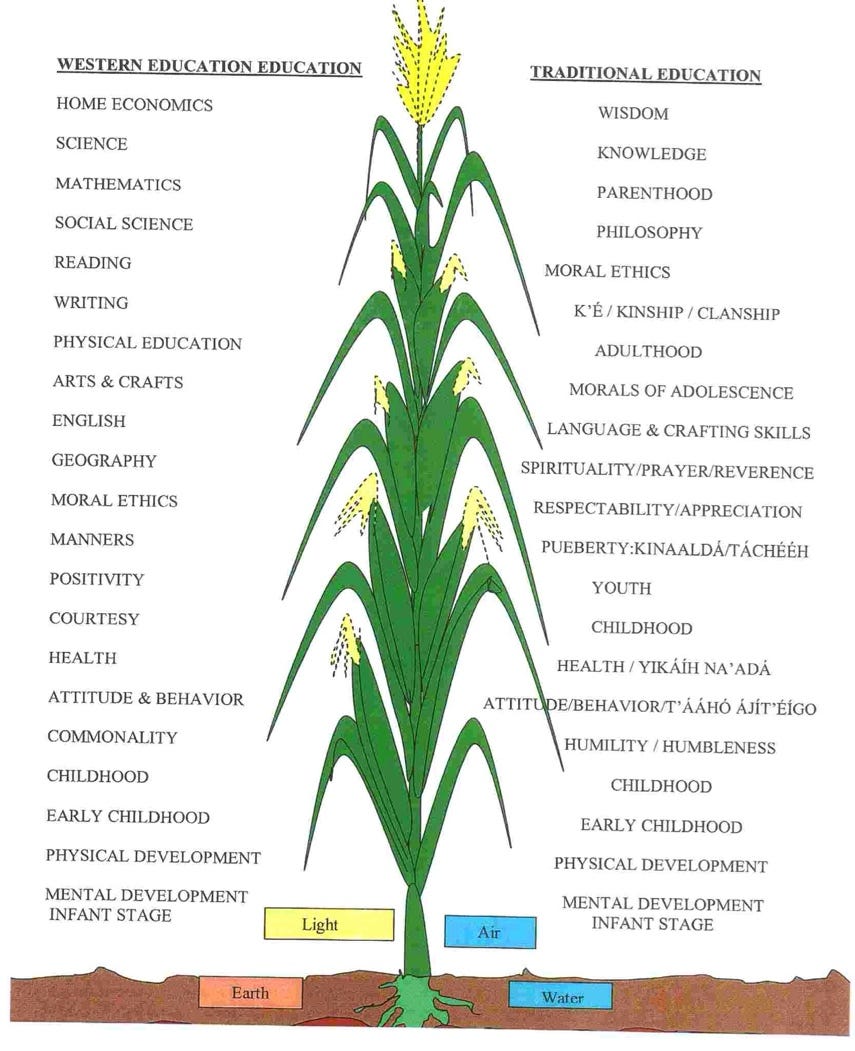

Take the word toes, for example. The Navajo word for toes could best be translated as “little pigs sitting on a fence”. The model is that of the sacred cornstalk, growing from the ground up. Corn symbolizes birth, growth and development, as well as life’s dependence on earth and water (below ground) as well as light and air (above ground).

This model is foundational to the Peacemaking Program of the Judicial Branch of the Navajo Nation. Roger Begay has written about the distinction between Diné and bilagáana in how they respect themselves: [2]

(The) Native has appreciation and respect for himself in his existence in accordance to his Creator, Mother Earth and the Universe. He acknowledges reverence and assures himself to his Creator by offering white cornmeal in prayer while anointing himself from the palms of his feet and upwards to the top of his head in the process. He acknowledges his spatial existence, his sacred name by offering to Mother Earth, the Universe, the cardinal directions, the environment in sacred places such as the mountains and nature before he acknowledges himself as a human being. . .

The Caucasian generally is more in the mode for the mind, stimulating and educating the mind to prosper, seemingly more a form of a goal to achievement: the will to survive and prosper with all the goodness (of) money, a well-to-do life, nice home, forms of travel, jewelry, and attainment of power. Respect for the Earth and the environment is secondary in importance to wealth and prosperity, where spirituality comes in the form of worship on Sundays and Wednesdays.

It is more difficult to separate linguistics and cultural philosophy with the Navajo language than with other languages I have studied. I also found it hard organize the language in a way that made sense to me. Finally, I found it difficult to stay focused for two hours every Monday at the end of the workday. My performance reflected those difficulties. I would have been pleased to receive an average grade on assignments or tests. I rarely achieved even that modest goal.

I don’t know whether it was from frustration or fatigue, but I ultimately spoke to Teddy Draper about my decision to withdraw from his course. He was understanding, gracious, and – in the mode of an enthusiastic teacher – he encouraged me to make another attempt to learn the language at a later time when circumstances were more favorable.

The impression that Teddy Draper left with me was profound. I had never before been defeated by something that – on the surface – seemed so straightforward. But I learned a great deal about the limitations that our world view often imposes upon us. And I learned a great deal about people – including myself – in the process.

Teddy Draper was a devoted teacher who had a passion for his culture, for his people, and for helping them understand who they are in this world. In addition, he was a hero – to both the Diné and to bilagáanas. He had been a Navajo Code Talker[3] during World War II.

Teddy Draper was born in 1923, a year after my own father, who also fought in the Pacific during World War II. Draper grew up in Chinle, Arizona, about 40 miles north of Ganado where I attended his classes. He enlisted in the Marines as a teenager, and he was among those who fought against the Japanese in the Battle of Iwo Jima. Even after sustaining an injury early in the battle, he helped our soldiers retake this small island that had been heavily fortified by the Japanese but was essential for the Allies to secure. And he communicated – in the inscrutable Navajo code that was never broken[4] – critical information that was necessary for the U.S. Marines and Navy to ultimately win the 36-day assault on Iwo Jima in March 1945 at the cost of 6800 American lives.[5]

Today there are abundant resources – textbooks, online courses, and videos – in addition to excellent classroom teachers to teach Diné bizaad. But in my mind, much of the credit goes to educators like Teddy Draper for preserving the context and the culture of the Navajo language. It was my privilege to have had him as a teacher.

Opa

[1] https://www.omniglot.com/writing/navajo.htm

[2] https://courts.navajo-nsn.gov/Peacemaking/corntext.pdf

[3] https://guides.loc.gov/navajo-code-talkers/profiles/teddy-draper An extended interview about Teddy Draper’s upbringing on the Navajo Reservation is at https://www.c-span.org/video/?459510-1/navajo-code-talker-teddy-draper-oral-history-interview

[4] https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/navajo-code-talker-dictionary.html