Gram and I have friends who recently set out on a pilgrimage to Iona, an island of the Inner Hebrides west of Scotland. They are following the journey of Columba, an Irish monk who around 563 A.D. set out to evangelize Scotland and England. Iona is where Columba and his dozen followers built an Abbey from which they reached out to share the Christian faith with the Picts. This island is considered the birthplace of Celtic Christianity. It is known as a “thin place” by many Christians – a place where or a moment when the perceived distance between heaven and earth is diminished, and God’s presence feels especially close. Iona is respected as a place for spiritual renewal – a place that drives one’s heart forward rather than keeping one’s eyes looking back. The landscape is beautiful and austere, and the Abbey sits looking west across the Atlantic Ocean towards the southern coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

In July, 2017, Gram and I also went on a pilgrimage to learn more about Celtic spirituality. I can say without equivocation that this trip was more pivotal, than any we have ever taken, in changing how we think about the world and our faith. We went to Durham, England – in the region previously known as Northumbria. I was excited to make this trip, knowing that (on every other of our ten days) there would be excursions to important sites marking the history of the Gospel’s spread in England. By the end of our time there, however, it was the alternate days of study, fellowship and prayer that held the greatest meaning for me and instilled the deepest memories.

I first developed an interest in the Celts when in the 1990’s I read Thomas Cahill’s book, How the Irish Saved Civilization. These people were confident, passionate, quick to embrace life and not afraid of death. The Celts were wild and dangerous people. I gained insight when I read G.K. Chesterton’s description quoted in Cahill’s book:

For the great Gaels of Ireland

Are the men that God made mad.

For all their wars are merry,

And all their songs are sad

They inherited their passionate Christian faith from Saint Patrick, who was captured during a raid by pagan Irish warriors when he was a teenager living near the west coast of Britain. He was forced into slavery and spent six years in captivity – cold, naked, and hungry, held by some minor Irish chieftain until he escaped. But he learned and respected many Irish values and behaviors, which led him to train as a priest and return to Ireland to share his own Christian faith. Patrick was unusual in many ways. He was the first Christian missionary to ever travel beyond the known, civilized world . . . and this was 400 years after St. Paul’s travels. Furthermore, he returned to the land of his enslavement. Since he had spent most of his formative years as a slave, he lacked a proper formal education in the classics. Thus, his approach was to love people first – not to instruct them, and then to gradually share his faith. This became a hallmark of Celtic outreach, turning the “standard” approach to evangelism on its head.

Over the years, Gram and I observed that the traditional or “Roman” way of bringing people to faith (a strategy sometimes still used) is based on the sequence: BEHAVE - BELIEVE - BELONG. In other words, conform your behavior to the church’s expectations of what a Christian should be. Then believe certain doctrines that the Church has established, which may never have been taught by Jesus or was an expansion beyond what Jesus actually taught. Then, finally, you can belong to the inner circle of the Christian “us” as opposed to the “others,” for as long as you adhere to a prescribed set of beliefs and actions, demonstrating fidelity and fealty to church leadership. This sequence is not unique to just the Roman Catholic Church; it is the model for many Protestant sects that are offshoots. However, the Celtic sequence is quite different. It is: BELONG - BELIEVE - BEHAVE. On our pilgrimage, one person suggested that BEHOLD would be another word to describe one’s journey of coming to faith.

The starting point is that all people and all nature were created by God, and we are therefore His already. We belong to Him (not the church) now, whether or not we know it or acknowledge it. The next step is to behold what God has created and what he has done. Many of us are blind to the glories around us and blind to the good in people around us (especially those who are unlikable or who fail to believe or live as one thinks they should). If we see creation as God does, then that alerting of our senses, that appreciation of His brilliance in creation, can lead to a curiosity in and pursuit of God. This allows us to grow a faith in God. This inspires us, educates us, and encourages us in becoming more Christ-like as we try to live out our faith. “Behaving” is a natural outgrowth of our desire to live a better life rather than a prerequisite for becoming part of the inner circle. For the Celts, there is no circle that you are within or without.

I find it interesting that there were very few martyrs among Celtic Christians, while there are many among the Roman Christians. The Celts believed in the power of God but they were not power-driven. They knew how to relate to the people they loved; they looked for the good in people and tried to bring it out. Celtic Christians were welcoming, knowing that all people carry God’s goodness but are fallen. They thrived in the chaos around them. Christians of the imperial Roman tradition were anxious about man’s sin and eager that he be redeemed. They required perfection, order and obedience. Unlike St. Augustine, who was worldly, pessimistic, and saw nothing good in people, Celtic Christians were ascetic, spiritual, and believed that Jesus came to complete God’s good creation. Celtic Christians were not threatened by pagan religions. They saw that God was bigger than the pagan world.

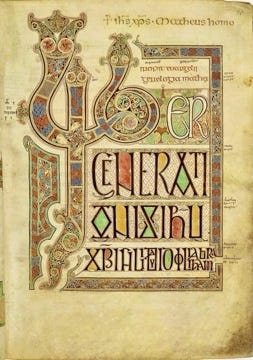

Why did Gram and I travel to Durham, rather than to Iona? St. Columba never went to Durham. But, from among Irish monks who studied under him while living at Iona Abbey, Columba sent Aiden to Northumbria (the northern part of England that borders Scotland). This was at the request of King Oswald, who wanted to restore the Christian faith that had slipped back to Anglo-Saxon paganism after the departure of the Romans from early England.[1] In 635 AD, Aiden founded a monastery at Lindisfarne in Northumbria. It is known as the “Holy Island”, an island because - at high tide – Lindisfarne becomes an island; it can only be reached on foot at low tide. Directly east of Lindisfarne is the North Sea, and beyond that the southern border of Norway. Gram and I travelled there one rainy day to visit this holy site of asceticism, prayer, and missionary outreach – to the place where a remarkable illuminated manuscript, the Lindisfarne Gospels, was created between 715 and 720 AD.[2]

Lindisfarne became the spiritual and missionary center of Christian growth in England, but it was undefended. On June 8, 793, Vikings destroyed the church on the Holy Island, slaughtering many of its unarmed monks and pillaging the church’s relics.[3] It was a watershed moment in European history, marking the onset of frequent Viking attacks.

The community of survivors moved several times over the next two centuries, each relocation forced by more Viking raids. In 995 the monks ultimately moved to an easily defensible hill surrounded on three sides by a loop of the River Wear. On the top of this hill, they established what became the city of Durham, about 80 miles south of Lindisfarne.

The Durham that Gram and I visited – 1022 years after the monks from Lindisfarne arrived – captures centuries of England’s spiritual, military and political history. Today it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[4] On our first night, we stayed in Durham Castle, built by William the Conqueror. On subsequent nights we stayed in a residence at St. Chad’s College of Durham University, adjacent to Durham Cathedral. It is easy to be distracted by the scope of history and the majesty of architecture that characterizes this town. But we were there with a small group of people, led by Pastors Doug and Adele Calhoun and Rev. Susie Skillen, who guided us in exploring the lives and spirituality of leaders of the Celtic Church in the 6th to 8th centuries. Our time was grounded in rhythm of English breakfasts, daily fellowship and prayer, and exploring the beauty of Creation. It was a time of retreat, meditation and growth – and an antidote to the busyness of life that too often separates us from others.

I find in writing this, that I am far from the end of telling the important parts of our pilgrimage and study of Celtic spirituality. Because this has been so important to Gram and me, my plans are to continue our story in at least one more letter. With the hope that you – our grandchildren – will someday set out on a similar journey, I’ll close with a Celtic prayer, recently shared with me by our friends during their pilgrimage:

Be Thou a smooth way before you,

Be Thou a guiding star above you,

Be Thou a keen eye behind you,

This day, this night, for ever . . .

If only Thou, O God of life,

Be at peace with you, be your support,

Be to you as a star, be to you as a helm,

From your lying down in peace to your rising anew.

Opa

[1] See: https://www.lindisfarne.org.uk/general/oswald.htm and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aidan_of_Lindisfarne

[3] http://www.churchsidefederation.norfolk.sch.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Lindisfarne-Reading-Comprehension.pdf

No wonder I like you two so much ch and found such affinity the first time we met on the beach . Thank you for this fascinating entry. Rich in every sentence and deeper still in the spaces between the paragraphs.