When I was young, people referred to the Middle Ages as the “Dark Ages”, suggesting that there was no advancement or scholarship between the fall of the Roman Empire and the emergence of Christian Europe. Over the years since Gram and I went on our Celtic pilgrimage, however, I have thought much about the dedicated people who had particularly important roles during these years. While we were in Northumbria, we learned that, during the 7th century, one such spiritual leader was Hild, now known as St. Hilda.

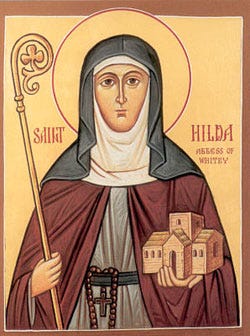

She was born in 617 A.D. and raised by her uncle, King Edwin, after her father was murdered. When her older sister went to France to become a nun, Hild was asked by Aiden, the Abbot of Lindesfarne who recognized the strength of her holiness, to remain in Northumbria and work for the conversion of its people to Christianity. Hild was given a small amount of land north of the Wear River. After a period of time, because of her demonstrated intellect, devotion, and effectiveness as an administrator, she was asked to establish and become Abbess for a monastery at Whitby, located on the coast about 60 miles southeast of what would later become Durham. This was a dual monastery - for both men and women.

Celtic Christians were unique among Europeans in that they encouraged collaboration between men and women as equals. Their Trinitarian view allowed women to possess an undiminished role in society. At various times, women were elected as clan chiefs, led fighters into war, exercised spiritual leadership, and established monastic communities. (Among the Picts in northern England and Scotland, the line of inheritance passed through women, not men.) Whereas, in cultures under Roman influence a wife was considered to be property.

Whitby was to become one of the most respected and powerful monasteries in England. Hild ultimately trained five men who went on to become bishops. Also, it was in her monastery, where a man who initially only cared for animals became famous as a poet. This man, Caedmon, wrote the oldest existing poem, or hymn, in the English language.[1] Like other Celts, Hild considered the senses to be part of intellect and regarded the arts as higher learning; what the eyes saw and the ears heard were considered good sources of instruction. The Celts saw truth as more than facts; it was anything that opened the mind to God, to the persons of the Holy Trinity. Capturing the symbolism of birds as messengers, creating jewelry with three-fold cords reflecting the Trinity, and using Celtic crosses as prayer-stones at property boundaries were all intended to link heaven and earth; to create designs without beginning or end; to portray truth, joy, and celebration of faith and life.

Hild acquired a reputation for her leadership, scholarship and statesmanship. Manuscripts and commentaries produced at monasteries under her direction “were intended not so much to reflect as to shape a Christian culture.”[2] She was often asked to resolve differences that arose between spiritual as well as political leaders; she was known as a “peace-weaver”. In 664, the king of Northumbria convened a council at her monastery in Whitby that would define the future of the English church. The purpose was to resolve differences between Celtic Christian practices in the northern part of England and Roman Christian practices in the southern part of England. Hoping to again extend Rome’s influence to England, Pope Gregory the Great 68 years earlier - in 596 - had sent a missionary delegation led by Augustine, a prior from an abbey in Rome, to Canterbury, the capital of Kent.

The monastery at Whitby was attacked in the Viking raids of 793, and the abbey was completely destroyed by Danish invasions in 867. The church was rebuilt in the 11th century. Gram and I, together with our fellow sojourners, visited Whitby; there was nothing to see from the original monastery, but we could best describe this site as “a thin place”.

What aspects of Celtic spirituality have lived on after the Council of Whitby and the gradual ascendence of Roman influence? There remained the belief that all things only exist in relationship, with interdependence and vulnerability – that nothing can exist in its own self. Relatedness remained the goal of human history, and the central vision in the new heaven and the new earth:[3]

God’s dwelling is here, with humankind. He will dwell with them, and they will be His peoples. God himself will dwell with them as their God.

Gram and I returned home with a new perspective – a more optimistic spirituality – and a sense that, no matter where we go, we are living in the shadow of sacred spaces. Our role is not as much to change things as to consecrate things, to consider everything and everyone as part of God’s dominion, and to find meaning in both bad and good experiences.

It is not difficult to find applications for a Celtic spirituality in our society today. While some people seem to be floating easily down the river, others feel like they are struggling to swim upstream. One lesson from our pilgrimage was that people’s visions of life may be too narrow or too “in the moment”. Since our pilgrimage, I have understood that God’s world is much greater – greater in expanse, depth, challenge, and opportunity than we have imagined. It is as if we have been travelling on a river, but we are now sailing on the sea.

Words are powerful, but music can be even more so. In closing, I encourage you to carefully listen to the words and music of the Celtic hymn “Be Thou My Vision”. . . and feel the message and spirit of the Celtic Christians.[4]

Opa

[1] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/159193/caedmon39s-hymn

[2] Anne Inman, Hild of Whitby and the Ministry of Women in the Anglo-Saxon World, Fortress Academic, 2019.

[3] Revelation 21:3, Common English Bible

Really enjoyed these two post so much. I’d love to go here with you all next year!