I watched tears slowly roll from my grandmother’s eyes and it left me puzzled. Together, with the rest of my family, we were singing hymns in church. As a young teenager, I had only recently – after her retirement and relocation to Colorado – enjoyed having her live nearby. I was close to her and admired her gentle, kind disposition. “What’s wrong, Grandma?” I whispered to her. She reassured me, saying it was nothing. I wasn’t sure whether to believe her or not, knowing that she never wanted to draw attention to herself. She had been raised as an only child by a mother with a volcanic temper; she had been widowed only a decade into her marriage and had lost her husband’s financial holdings to his sister; and she had single-handedly raised their sensitive, easily-offended child who became my mother.

I observed these tears over and over again during the last three years of my grandmother’s life, and she was steadfast in saying that they were triggered by the worshipful music that she heard. Decades later, I was with my own mother the day before she died. She could no longer speak and rarely opened her eyes. But from my phone placed near her ear, I played some music that I knew was dear to her. My mother never spoke nor appeared to awaken, but tears rolling down her cheeks were evidence to me that she heard, understood and appreciated the music.

At some point, I began to occasionally have similar experiences myself with certain hymns or other types of music that that evoked a sense that I can best describe as joy or being overwhelmed by sublime beauty. It was more than and very different from a kindling of memories. It was a visceral appreciation of what I was hearing – a communion with a composer or song-writer who crafted certain melodies that penetrated to my core. It was a “heart-felt” response affecting me physically as well as emotionally.

These events seemed unique to me. Not because it was necessarily uncommon, but because I had no reason to expect the melody or song should affect others in the same way. One example, for me, came from the now obscure 19th century Hungarian composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel, who was a student of Mozart.[1] His Piano Concerto in A minor (Opus 85) is brilliant. I enjoy the first movement, Allegro. But the melodiousness of the third movement, Rondo, exceeds anything that I have ever heard.[2]

The most enduring example of a nearly unanimous response to a musical piece that I can think of over the last 300 years is George Frederick Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” at the end of his oratorio Messiah. The reason that people rise and stand during the singing of the Chorus is uncertain. During my childhood, I was told this was because King George II stood upon hearing it during the oratorio’s London debut in 1745.

Perhaps today – like Handel’s Messiah – the music sung by Celine Dione and Josh Groban[3] or by Dolly Parton[4] brings tears to the eyes of many listeners because of their powerful voices or their poignant lyrics.

These events, regardless of what melodies or passages in music trigger them, are examples of an undeniable interplay between hearing, emotions and a physical reaction. Also, “chills” or “goosebumps” can occur when people hear certain passages of music. This is an involuntary phenomenon called frisson (pronounced “freeze-on”), a French word for shiver; and it is accompanied by the standing up of hairs on your skin. It’s what Jennifer Lopez calls “goosies”.[5]

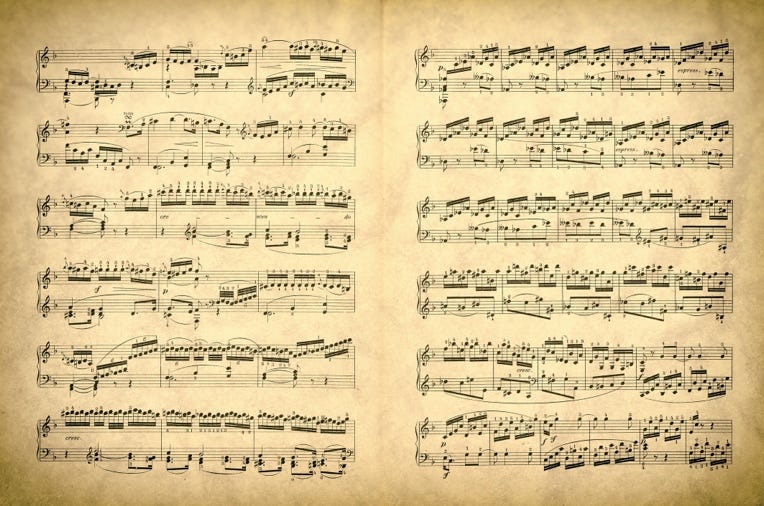

My first experience of this was in high school. I mostly listened to classical music – particularly music for piano, which was the instrument that I played. A short piece – about a minute longer than Freddy Mercury’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” – that captivated me and caused frisson was the Polonaise in A-flat major (Opus 53), written by Frederick Chopin in 1842.[6] Containing melodies from his Polish homeland as well as exhilarating harmonies that give way to bursts of restlessness, it builds again and again to periods of power and brilliance. George Sand (the pen name of the woman he lived with) called this composition his “Heroic Polonaise”, because it seemed to convey the resilience and courage of Poland, which at the time had ceased to exist as a country and had been divided between Russia, Prussia and Austria.[7]

Every time I listened to this piece of music, chills travelled from my lower back to my neck, and the hairs on my arms stood on top of goosebumps. I was determined to learn and master this piece. Over time, I did. . . but it was interrupted by college and then medical school (when my roommates swore that practicing made my playing no better). What I noted, however, was that as my technical proficiency improved, the frisson was gone. I suppose my interpretation of the music moved from my right brain to my left brain. The sound and the power of the music remained the same, but the emotional and physical response to it diminished. That surprised and then saddened me.

Now, I hear this same music and the frisson has been supplanted by tears. How ridiculous this sounds, as I tell about it! But there are a few lessons to learn from all this. First, music is a powerful and universal language, but everyone – even within a given culture – uses it and reacts to it differently. Neuroscientists have learned that music that is pleasurable leads to the release of dopamine. Music that causes frisson creates an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, and our body shifts into the “fight or flight” mode. Tears, on the other hand, are associated with slowing of the heart rate, part of the parasympathetic nervous system activity, shifting us into the “rest or digest” mode. Either way, there is a direct connection between our emotional experiences or thoughts and our body’s physical responses.

Second, I understand that these reactions vary tremendously from one person to another. I cannot expect others to hear or feel or respond the way I do. If that is true with something as “universal” as music, it must be even more so with other things that reside in the gulf between knowledge and emotion, or across the bridge between understanding and feelings.

Finally, it has become clear to me that we all evolve during the course of our lives. For me, learning the mechanics of performing Chopin’s “Heroic Polonaise” has changed my chills to tears. And just living longer has brought the sweet sadness of tears to so many more experiences in my life.

Opa

[1] Hummel was named after John of Nepomuk, a martyred saint of Bohemia. While Hummel was studying piano with Mozart, he was invited to live with Mozart for two years. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Nepomuk_Hummel

[2] Listen on Spotify at https://spoti.fi/43ua2kn or on YouTube at

[6] Listen at:

or

[7] It is worth learning about the history of Poland, which – after the creation of our own country in the late 1700’s – ceased to even exist as a country for over 120 years. To understand how the Polish people rebuilt their country, read: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Poland_(1795%E2%80%931918)